Excerpts of the book Critical Path by R. Buckminster Fuller

St. Martin's Press, 1981 - hard cover, 1st edition

Chapter 3

Legally Piggily

I'M GOING TO REVIEW my prehistory's

speculative assumptions regarding the origins of human power

structures.

In a herd of wild horses there's a king

stallion. Once in a while a young stallion is born bigger than

the others. Immediately upon his attaining full growth, the king

stallion gives him battle. Whichever one wins inseminates the

herd. Darwin saw this as the way in which nature contrives to

keep the strongest strains going. This battling for herd kingship

is operative amongst almost all species of animal herds as well

as in the "pecking order" of flocking bird types.

I'm sure that amongst the earliest of

human beings, every once in a while a man was born much bigger

than the others. He didn't ask to be—but there he was. And

because he was bigger, people would say—each in their own

esoteric language—"Mister, will you please reach one

of those bananas for me, because I can't reach them." The

big one obliges. Later the little people would say, "Mister,

people over there have lost all of their bananas and they are

dying of starvation, and they say they are going to come over

here and kill us to get our bananas. You're big—you get

out in front and protect us." And he would say, "OK,"

and successfully protect them.

The big one found his bigness continually

being exploited. He would say to the littles, "Between these

battles protecting you, I would like to get ready for the next

battle. We could make up some weapons and things." The people

said, "All right. We'll make you king. Now you tell us what

to do." So the big man becomes king quite logically. He

could have become so in either a bullying or good-natured way,

but the fact is that he was king simply because he was not only

the biggest and the most physically powerful but also the most

skillful and clever big one.

Every once in a while along would come

another big man. "Mr. King, you've got things too easy around

here. I'm going to take it away from you." A big battle

ensues between the two, and after the king has his challenger

pinned down on his back, he says, "Mister, you were trying

to kill me to take away my kingdom. But I'm not going to kill

you because you'd make a good fighter, and I need fighters around

here to cope with the enemies who keep coming. So I'm going to

let you up now if you promise to fight for me. But don't you

ever forget—I can kill you. OK?" The man assents, so

the king lets him up.

But instinctively the king says secretly

to himself, "I mustn't ever allow two of those big guys

to come at me together. I can lick any one of them, but only

one by one." The most important initial instinct of the

most powerful individual or of his organized power structure

is, "Divide to conquer, and to keep conquered, keep divided."

So our special-case king has now successfully

defended his position against two or more big guys who are all

good fighters. He makes one the "Duke of Hill A," the

second "Duke of Hill B," and the third "Duke of

Hill C," and tells each one to "mind your own business"

because "only the king minds everybody's business,"

and he has his spies watch them so that they can't gang up on

him. Thus, our considered king is doing very well in his tribe-defending

battles.

However, there are a lot of little nonfighting

people who are not obeying the king regarding preparations for

the next fighting period. The king says to his henchmen, "Seize

that mischievous little character over there who is really being

a nuisance around here." To the prisoner the king says,

"I'm going to have to cut your head off." The man says,

"Mr. King, you'd make a big mistake to cut my head off."

The king asks, "Why?" "Well, I'll tell you, Mr.

King, I understand the language of your enemy over the hill,

and you don't. And I heard him say what he is going to do to

you and when he's going to do it." "Young man, you've

got a good idea at last. You let me know every day what my enemy

over the hill says he is going to do and so forth, and your head

is going to stay on. In addition, you're going to do something

else you've never done before. You're going to eat regularly

right up here in the castle near me. And I'm going to have you

wear a royal purple jacket (so that I can keep track of you)."

The king now has that little man under control and useful. Then

another little man makes trouble for the king. As he is about

to be beheaded, he shows the king that he understands metallurgy

and can make better swords than anybody else. The king says,

"You better make a good sword in a hurry." The man

makes a beautiful, superstrong, and sharp sword—there's

no question about that. So the king says, "OK, your head

stays on. You, too, are to live here at the castle."

Next, under the threat of beheadment,

another man making trouble for the king says, "The reason

I am able to steal from you is because I understand arithmetic,

which you don't. If I do the arithmetic around here, people won't

be able to steal from you." The king makes him court mathematician.

As each of these men are given those

special tasks to do for life, the king says to all of them, "Each

of you mind only your own business. You, Mr. Languageman, mind

only your own business; and you, Mr. Swordmaker, mind only your

own business; and you, Mr. Arithmetic, mind only your own business.

Each one minds only his own business. I'm the only one that minds

everyone's business. Is that perfectly clear?" "Yes

sir." "Yes sir." "Yes sir."

The king now has his kingdom operating

very well. He has great fighters, superior metallurgy, better

arithmetic and logistics, better spying and intelligence. His

kingdom is growing ever bigger. Years go by, and these experts

are getting old. The king says, "I want to leave this kingdom

to my grandson. Mr. Languageman, I want you to pick out and teach

some younger person about language. You, Mr. Swordmaker, I want

you to pick out and teach somebody about metallurgy. You, Mr.

Arithmetic, I want you to pick out and teach someone about arithmetic."

And his total strategy became the pattern for the ultimate founding

of Oxford University.

The way the power structure keeps the

wit and cunning of the intelligentsia—who are not musclemen,

who cannot do the physical fighting—from making trouble

for the power structure (if the intelligentsia are too broadly

informed, unwatched, and with time of their own in which to think)

is to make each one a specialist with tools and an office or

lab. That is exactly why bright people today have become streamlined

into specialists.

Nobody is born a specialist. Every child

is born with comprehensive interests, asking the most comprehensively

logical and relevant questions. Pointing to the logs burning

in the fireplace, one child asked me, "What is fire?"

I answered, "Fire is the Sun unwinding from the tree's log.

The Earth revolves and the trees revolve as the radiation from

the Sun's flame reaches the revolving planet Earth. By photosynthesis

the green buds and leaves of the tree convert that Sun radiation

into hydrocarbon molecules, which form into the bio-cells of

the green, outer, cambium layer of the tree. The tree is a tetrahedron

that makes a cone as it revolves. The tree's three tetrahedral

roots spread out into the ground to anchor the tree and get water.

Each year the new, outer-layer, green-tree cone revolves 365

turns, and every year the tree grows its new tender-green, bio-cell

cone layer just under the bark and over the accumulating cones

of previous years. Each ring of the many rings of the saw-cut

log is one year's Sun-energy impoundment. So the fire is the

many-years-of-Sun-flame-winding now unwinding from the tree.

When the log fire pop-sparks, it is letting go a very sunny day

long ago, and doing so in a hurry." Conventionally educated

grown-ups rarely know how to answer such questions. They're all

too specialized.

If nature wanted humans to be specialists,

she would, for instance, have given them a microscope on one

eye, which is what nature has done with all other living organisms—other

than humans. Each has special, organically integral equipment

with which to cope successfully with special conditions in special

environments. The low-slung hound to follow the Earth-top scent

of another creature through the thickets and woods . . . the

little vine that can grow only along certain stretches of the

Amazon River . . . the bird with beautiful wings with which to

fly, which bird however, when landed and in need of walking,

is greatly hampered by its integral but now useless wings.

Humans are not unique in possessing brains

that always and only are coordinating and storing for later retrieval

the integrated information coming in from each and all the creature's

senses—visual, aural, tactile, and olfactory. Humans are

unique in respect to all other creatures in that they also have

minds that can discover constantly varying interrelationships

existing only between a number of special case experiences as

individually apprehended by their brains, which covarying interrelationship

rates can only be expressed mathematically. For example, human

minds discovered the law of relative interattractiveness of celestial

bodies, whose initial intensity is the product of the masses

of any two such celestial bodies, while the force of whose interattractiveness

varies inversely as the second power of the arithmetical interdistancing

increases.

The human mind of Bernoulli discovered

the mathematical expression of the laws of intercovarying pressure

differentials in gases under varying conditions of shape and

velocity of gas flow around and by interfering bodies. The Wright

brothers' wing foils provided human flight, but not the information

controlling the mathematics of varying wing foil conformations.

Bernoulli's work made possible the mathematical improvement in

speed and energy efficiency of various wing designs. Human mind's

access to the mathematics of generalized scientific laws governing

physical phenomena in general made possible humanity's production

of its own detached-from-self wings to outfly all birds in speed

and altitude, while being able to loan one another those wings

and modify them to produce even better wings.

I'm sure our human forebears went

through quite a period of giants and giant-affairs evolution.

These probably led to all sorts of truth-founded legends from

which fairy stories were developed, many of which are probably

quite close to the facts of unwritten history. Then humans developed

to the point at which a small man made a weapon, a stone-slinger,

such as in the story of David and Goliath, with which the little

man slays the big man by virtue of a muscle-impelled missile.

At the U.S. Naval Academy "ballistics" is defined as:

the art and science of controlling the trajectory of an explosively

buried missile. After the sling and spear we got the bow and

arrow with which a small man could kill a big man at much greater

distance than with spear or sling. So skill and human-muscle-impelled

weapons ended the era of giants.

Discovery of energetic principles, and

human inventiveness in using those principles, such as the invention

of catapults and mechanically contracted, steel-spring-coil arrow

impelment, advanced the art of weapons. The human power structures

that could best organize and marshal the complex of interessential

"best" weapons and support an army of best-trained

people with each of the special types of weapons were the ones

who now won the battles and ran the big human "show."

The discovery of gunpowder by the Chinese and the invention of

guns introduced the era of ballistics, or as the Navy terms it,

"explosively hurled missiles."

Going back to the stone-sling, bow-and-arrow,

spear, club, and knife era of weapons, we find that territorial

battles between American Indian nations were fought over the

local hunting and fishing rights, but the land itself always

belonged to the Great Spirit. To the Indians it was obvious that

humans could not own the land. There was never any idea that

the people could own land—owning was an eternal, omniscient

omnipotence unique to the greatness, universality, and integrity

of the forever-to-humans-mysterious Great Spirit. Until a special

human-produced change in the evolution of power structures occurred,

the ownership of anything being unique to the Great Spirit—in

whatever way that might be designated by local humans—was

held by all people around our planet.

In 1851 Seattle, chief of the Suquamish

and other Indian tribes around Washington's Puget Sound, delivered

what is considered to be one of the most beautiful and profound

environmental statements ever made. The city of Seattle is named

for the chief, whose speech was in response to a proposed treaty

under which the Indians were persuaded to sell two million acres

of land for $150,000.

How can you buy or sell the sky, the warmth of the land? The idea is strange to us.

If we do not own the freshness of the air and the sparkle of the water, how can you buy them?

Every part of this earth is sacred to my people. Every shining pine needle, every sandy shore, every mist in the dark woods, every clearing and humming insect is holy in the memory and experience of my people. The sap which courses through the trees carries the memories of the red man.

The white man's dead forget the country of their birth when they go to walk among the stars. Our dead never forget this beautiful earth, for it is the mother of the red man. We are part of the earth and it is part of us. The perfumed flowers are our sisters; the deer, the horse, the great eagle, these are our brothers. The rocky crests, the juices in the meadows, the body heat of the pony, and man—all belong to the same family.

So, when the Great Chief in Washington sends word that he wishes to buy our land, he asks much of us. The Great Chief sends word he will reserve us a place so that we can live comfortably to ourselves. He will be our father and we will be his children.

So we will consider your offer to buy our land. But it will not be easy. For this land is sacred to us. This shining water that moves in the streams and rivers is not just water but the blood of our ancestors. If we sell you land, you must remember that it is sacred, and you must teach your children that it is sacred and that each ghostly reflection in the clear water of the lakes tells of events and memories in the life of my people. The water's murmur is the voice of my father's father.

The rivers are our brothers, they quench our thirst. The rivers carry our canoes, and feed our children. If we sell you our land, you must remember, and teach your children, that the rivers are our brothers and yours, and you must henceforth give the rivers the kindness you would give any brother.

We know that the white man does not understand our ways. One portion of land is the same to him as the next, for he is a stranger who comes in the night and takes from the land whatever he needs. The earth is not his brother, but his enemy, and when he has conquered it, he moves on. He leaves his father's grave behind, and he does not care. He kidnaps the earth from his children, and he does not care. His father's grave, and his children's birthright are forgotten. He treats his mother, the earth, and his brother, the sky, as things to be bought, plundered, sold like sheep or bright beads. His appetite will devour the earth and leave behind only a desert.

I do not know. Our ways are different from your ways. The sight of your cities pains the eyes of the red man. There is no quiet place in the white man's cities. No place to hear the unfurling of leaves in spring or the rustle of the insect's wings. The clatter only seems to insult the ears. And what is there to life if a man cannot hear the lonely cry of the whippoorwill or the arguments of the frogs around the pond at night? I am a red man and do not understand. The Indian prefers the soft sound of the wind darting over the face of a pond and the smell of the wind itself, cleansed by a midday rain, or scented with piñon pine.

The air is precious to the red man for all things share the same breath, the beast, the tree, the man, they all share the same breath. The white man does not seem to notice the air he breathes. Like a man dying for many days he is numb to the stench. But if we sell you our land, you must remember that the air is precious to us, that the air shares its spirit with all the life it supports.

The wind that gave our grandfather his first breath also receives his last sigh. And if we sell you our land, you must keep it apart and sacred as a place where even the white man can go to taste the wind that is sweetened by the meadow's flowers.

You must teach your children that the ground beneath their feet is the ashes of our grandfathers. So that they will respect the land, tell your children that the earth is rich with the lives of our kin. Teach your children that we have taught our children that the earth is our mother. Whatever befalls the earth befalls the sons of the earth. If men spit upon the ground, they spit upon themselves.

This we know: the earth does not belong to man; man belongs to the earth. All things are connected. We may be brothers after all. We shall see. One thing we know which the white man may one day discover: our God is the same God.

You may think now that you own Him as you wish to own our land; but you cannot. He is the God of man, and His compassion is equal for the red man and the white. This earth is precious to Him, and to harm the earth is to heap contempt on its creator. The whites too shall pass; perhaps sooner than all other tribes. Contaminate your bed and you will one night suffocate in your own waste.

But in your perishing you will shine brightly fired by the strength of the God who brought you to this land and for some special purpose gave you dominion over this land and over the red man.

That destiny is a mystery to us, for we do not understand when the buffalo are all slaughtered, the wild horses are tame, the secret corners of the forest heavy with scent of many men and the view of the ripe hills blotted by talking wires.

Where is the thicket? Gone. Where is the eagle? Gone.

The end of living and the beginning of survival."*

| *Chief Seattle's speech was submitted by Dr. Glenn T. Olds at Alaska's Future Frontiers conference in 1979. |

In my prehistory accounting I talk

about the time when each ice age is engaging an enormous amount

of the oceans' water, lowering the waterfront and bringing together

the islands of Borneo, the Philippines, and others, all to become

part of the Malay Peninsula. I also spoke of the ice cap pushing

the furry animals southward until they were suddenly pushed into

the land of the previous islands now formed into the new peninsula—into

land they could never before reach. This is how animals like

tigers got out to now-reislanded places like Bali. Human beings

suddenly confronted with these wild animals learned how to cope,

hunting some and taming others. In following the evolution of

human power structures we are now particularly interested in

the humans who found themselves confronted with a tidal wave

of wild animals. Those who were overwhelmed became aggressive

hunters, and those who were not overwhelmed became peaceful domesticators

of the animals. Some of the most aggressive men mounted horses,

moved faster than all others, and went out to seek the beasts.

We have learned in the last decade from

our behavioral science studies that aggression is a secondary

behavior of humans—that when they get what they need, when

they need it, Old are not overwhelmed, they are spontaneously

benevolent; it is only when they become desperate that they become

aggressive because what they have relied on is no longer working.

There are two kinds of social behavior manifest today around

the world—the benign and the aggressive. It is probable

that this dichotomy occurred in the human-versus-animal confrontation

in the ice age time.

When an ice age starts to recede, the

horsemen start north—hunting with clubs and spears. At the

same time, moving much more slowly, we have the beginnings of

great tribes of humans following their flocks of goats and sheep

as the latter lead them to the best pastures—sometimes high

on mountainsides, sometimes on great plains. With the big

man as king—the head shepherd—we have humanity

migrating off into a wilderness that seemed to have no limits.

The land belonged to the Great Spirit. The people lived on the

flesh of their animals and the encountered fruits, berries, nuts,

and herbs. They kept themselves warm with clothing made of the

skins of the animals and also with environment-controlling tents

made of local saplings and the animal skins.

We have a king shepherd, from the day

of the giants, tending his people and his flock, when along comes

a little man on a horse, with a club hanging by his side. He

rides up to the king shepherd and, towering above him, says,

"Well, Mr. Shepherd, those are very beautiful sheep you

have there. You know, it's very dangerous to have such beautiful

sheep out here in the wilderness. The wilderness is very dangerous."

The shepherd responds, "We've been out in the wilderness

for generations and we've had no trouble at all."

Night after night thereafter sheep begin

to disappear. Each day along comes the man on the horse. He says,

"Isn't that too bad. I told you it was very dangerous out

here. Sheep disappear out in the wilderness, you know."

Finally, there is so much trouble that the shepherd agrees to

accept and pay in sheep for the horseman's "protection"

and to operate exclusively within the horseman's self-claimed

land.

No one dared question the horseman's

claim that he owned the land on which the horseman said the shepherd

was trespassing. The horseman had his club with which to prove

that he was the power structure of that locale; he stood high

above the shepherd and could ride in at speed to strike the shepherd's

head with his club. This was how, multimillennia ago, twentieth-century

racketeers' "protection" and territorial "ownership"

began. For the first time little people learned how to become

the power structure and how thereby to live on the productivity

of others.

Then there came great battles between

other individuals on horses to determine who could realistically

say, "I own this land." Ownership changed frequently.

The ownership-claiming strategy soon evolved into horse-mounted

warfare as each gang sought to overwhelm the other. Then the

horse-mounted gangs, led by a most wily leader, used easily captured

human prisoners to build them stone citadels at strategic points.

Surrounded by prisoner-built moats rigged with drawbridges and

drawgates, they would come pouring out to overwhelm caravans

and others crossing their domains. "Deeds" to land

evolved from deeds of arms. Then came enormous battles of gangs

of gangs, and the beginning of the great land barons. Finally

we get to power-structure mergers and acquisitions, topped by

the most wily and powerful of all—the great emperor.

This is how humans came to own land.

The sovereign paid off his promises to powerful supporters by

signing deeds to land earned by the physical deeds of fighting

in shrewd support of the right leader. Thereafter emperors psychologically

fortified the cosmic aspect of their awesome power by having

priests of the prevailing religions sanctify their land-claiming

as accounted simply either by discovery or by arms.

In another set of events that opportuned

the power structure the land barons discovered the most geographically

logical trading points for caravaning: a place where one caravan

trail would cross another caravan trail; where, for instance,

the caravaners came to an oasis or maybe to a seaport harbor

and transfer some of their goods from the camel caravans to the

boats. The caravaners would say, "Let's exchange goods right

here. Fine. You need something; I have it."

One day they're exchanging goods when

along comes a troop of armed brigands on horseback. The head

horseman says, "It's pretty dangerous exchanging valuable

things out here in the wilderness." The caravaners' leader

says, "No, we never have any trouble out here. We have been

doing this for many generations." Then their goods begin

to be stolen nightly, and finally the merchants agree to accept

and pay for "protection." That was the beginning of

the walled city. The horse-mounted gangsters brought prisoners

along to build the city's walls and saw to it that all trading

was carried on inside the walls. The lead baron then gave each

of his supporters control of different parts of that city so

that each could collect his share of the "taxes."

This is how we came to what is called,

archeologically, the city-state, which was to become a very powerful

affair. There were two kinds: the agrarian-productivity-exploiting

type and the trade-route-confluence-exploiting type. These produced

all the great walled cities such as Jericho and Babylon.

The agrarian-supported city-state works

in the following manner: For example, we have Mycenae in Greece,

a beautiful and fertile valley. It is ringed around with mountains.

You can see the mountain passes from the high hill in the center

of the valley. At the foot of the high central hill there is

a very good well. So they build a wall around the citadel on

the top of that mid-valley hill and walls leading down to and

around the well so that they can get their water. When they see

the enemy coming through the passes, the Mycenaeans bring all

the food inside their walls and into their already-built masonry

grain bins. What they can't bring inside the walls, they burn—which

act was called "scorching the fields." The enemy enters

the fertile valley, but there's nothing left for them to eat.

The enemy army has to "live on its belly"—which

means on the foods found along their route of travel—and

is hungry on arrival in the valley. The people inside have all

the food. The people outside try to break into the walled city,

but they are overwhelmed by its height and its successfully defended

walls. Finally the people outside—only able to go for about

thirty days without food—get weaker and weaker, then the

people inside come out and decimate them.

This was the city-state. It was a successful

invention for a very long period in history. At the trade-route

convergences city-states operated in much the same way but on

a much larger scale with the siege-resisting supplies brought

in by caravans or ships. The city-states were approximately invincible

until the siege of Troy. Troy was the city-state controlling

the integrated water-and-caravaning traffic between Asia and

Europe near the Bosporus. It had marvelous walls. Everything

seemed to be favorable for its people.

Meanwhile in history, we have millennia

of people venturing forth on the world's waters—developing

the first rafts, which had to go where the ocean currents took

them; then the dugouts, with which they paddled or catamaraned

and sailed in preferred directions; and finally the ribbed-and-planked

ship, suggested to them by the stout spine and rib cage of the

whales, seals and humans—stoutly keeled and ribbed, deep-bellied

ships. With their large ships made possible by this type of construction,

sailors came to cross the great seas carrying enormous cargoes—vastly

greater cargoes than could be carried on the backs of humans

or animals. Ships could take the short across-the-bay route instead

of the around-the-bay mountain route.

The Phoenicians, Cretans, and the Mycenaeans,

together, in fleets of these big-ribbed and heavily planked ships,

went to Troy and besieged it. Up to this time the besiegers of

Troy had come overland, and they soon ran out of food. But the

Troy-besieging Greeks and Cretans came to Troy in ships, which

they could send back for more supplies. This terminally-turned-around

voyaging back to the supply sources and return to the line of

battle was called their "line of supply." The new line-of-supply

masters—the Greeks—starved out the Trojans. The Trojans

thought they had enough food but had not reckoned on the people

besieging them having these large ships. The Trojan horse was

the large wooden ship—that did the task of horses—out

of whose belly poured armed troops.

At this time the power structure of

world affairs shifts from control by the city-state to the

masters of the lines of supply. At this point in the history

of swiftly evolving, multibanked, oar- and sail-driven fighting

ships, the world power-structure control shifts westward to Italy.

While historians place prime emphasis on the Roman legions as

establishing the power of the Roman Empire, it was in fact the

development of ships and the overseas line of supply upon which

its power was built—by transporting those legions and keeping

them supplied. Go to Italy, and you will see all the incredibly

lovely valleys and great castellos commanding each of those valleys

such as you saw in the typical city-states, and you can see that

none of those walls has ever been breached. Also in Italy—in

the northeastern corner—is Venice, the headquarters of the

water-people. The Phoenicians—phonetically the Venetians—had

their south Mediterranean headquarters in Carthage in northern

Africa. In their western Mediterranean and Atlantic venturings

the Phoenicians became the Veekings. The Phoenicians—Venetians—in

their ships voyaged around the whole coast of Italy and sent

in their people to each castello, one by one. The Venetians

had an unlimited line of supply, and the people inside each castello

did not. The people inside were starved out. Thus, all of the

regional masters of the people in Italy hated the Venetians-Phoenicians-Veekings

who were able to do this.

There being as yet no Suez Canal, the

new world power structure centered in the ship mastery of the

line of supply finally forcing the Roman Empire to shift its

headquarters to Constantinople some ten centuries after the fall

of Troy. The Roman emperor-pope's bodyguards were the Veekings-Vikings,

the water-peoples' most powerful frontier fighters. The line

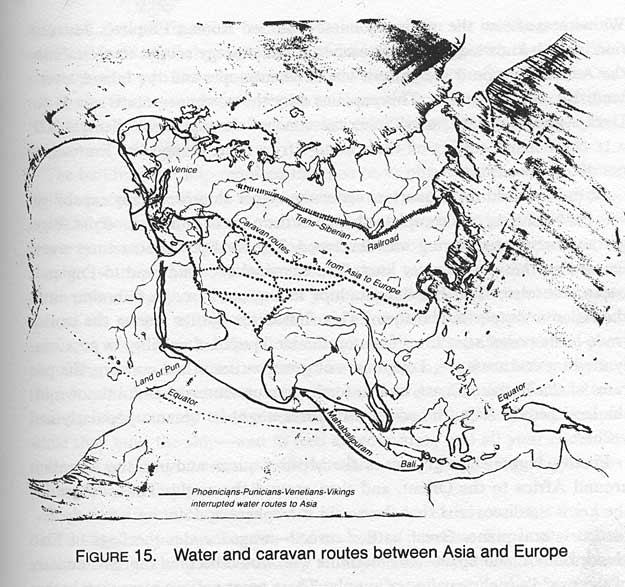

of supply from Asia to Constantinople was partially caravan-borne

and partially water-borne via Sinkiang-Khyber Pass-Afghanistan

or via the Sea of Azov, the Caspian and the Black seas. From

Constantinople, the western Europe-bound traffic was rerouted

from overland to waterway routes. Because the Asia-to-Constantinople

half of the trading was more land-borne-via-caravans, whose routes

were dominated by the city-state-mastering Turks, Constantinople

in due course was taken over by the Turks who established the

Byzantine Empire in the Aegean Sea and Asia Minor.

Before leaving the subject of the great

power-structure struggle for control of the most important, greatest

cargo-tonnage-transporting, most profitable, Asia-to-Europe trade

routes, we must note that the strength of the Egyptian Empire

was predicated upon its pre-Suez function as a trade route link

between Asia and Europe via the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, overland

caravan to the Nile, and then water-borne to Alexandria, or via

Somaliland, overland to the headwaters of the Nile, and thence

to Alexandria. The latter route was not economically competitive

but was the route of travel of the ship-designing and -building

arts that in due course brought the stoutly keeled, heavily ribbed,

big-bellied ships into the Mediterranean.

We have seen the Greek Alexander the

Great crossing Persia and reaching the Indian Ocean, thus connecting

with the Phoenician trading to Asia. A thousand years later the

Crusaders—ostensibly fighting for holy reasons—were

the Indian Ocean-Phoenician-Venetian-Veeking water-borne power

structure fighting the older overland-Khyber Pass power structure

over mastery of the trade route between Asia and Europe.

In our "Humans in Universe"

chapter we spoke about the 600-200 B.C. Greeks' discovery that

our Earth is a sphere and a planet of the solar system. This

was the typical scientific product of a water-navigation people.

We witnessed also the originally horse-mounted Roman Empire's

destruction of such knowledge, as their earlier grand strategy

sought to reestablish the Asia-to-Europe trade pattern via Constantinople

and the inland, overland, Khyber Pass route. This explains why

the power structure saw fit to Dark-Age-out the mariners' spherical

concept. It explains Ptolemy's 200 A.D. conic map's cutting off

the around-Africa route mapped by Eratosthenes 400 years earlier.

With the world three-quarters water the

bigger ship-producing capability was the beginning of a complete

change in the control of human affairs. Bigger and better engineering

was developed. The rival power structures were focused on the

water supply lines. The Romans' overland road to England became

obsolete. The Phoenician ships sailing out through Gibraltar

into the Atlantic outperformed them. This shifted the battles

among the world trade-route power structures from on-the-land

popular visibility to popularly unwitnessed seascape. Long years

of great battles of the corsairs, the pirates of the Barbary

Coast, and so forth were unwitnessed and unknown to the land

people. Who the power structures might be became popularly invisible.

Finally, bigger ships got out of the

Mediterranean and into the Atlantic, around Africa to the Orient,

and then around the World. Thus, "those in the know"

rediscovered that the world is a sphere and not an infinitely

extended lateral plane. Great battles ensued—waged under

the flags of England, France, and Spain—to determine who

would become supreme master of the world's high-seas line of

supply. These great nations were simply the operating fronts

of behind-the-scenes, vastly ambitious individuals who had become

so effectively powerful because of their ability to remain invisible

while operating behind the national scenery. Always their victories

were in the name of some powerful sovereign-ruled country. The

real power structures were always the invisible ones behind the

visible sovereign powers.

Because the building of superior fleets

of ships involved a complex of materials to produce not only

the wooden hulls but the metal fastenings and the iron anchors

and chains and the fiber ropes and cloth sails, and because woods

from many parts of the world excelled in various functions of

hull, masts, spars, oars, etc., large money credits for foreign

purchase of these and other critical supplies brought control

of the sea enterprising into the hands of international bankers.

The building of invisible world-power-structure

controls operates in the following manner. Suppose you know how

and have the ambition, vision, and daring to build one of these

great ships. You have the mathematics. You have the positioning

of numbers that enables you—or your servants—to calculate

the engineering data governing the design of hulls, spars, rigging,

etc., and all the other necessary calculations for the building

of a ship capable of sailing all the way to the Orient and returning

with the incredible treasures that you have learned from travelers

are to be found there. One trip to the Orient—and a safe

return to Europe—could make you a fortune. "There are

fabulous stores of treasures in the Orient to be cashed in—if

my ship comes in!"

The building of a ship required that

you be so physically powerful a fighting man—commanding

so many other fighting men as to have a large regiment of people

under your control—that you must have the acknowledged power

to command all the people in your nation who are carpenters to

work on your ship; all your nation's metalworkers to work on

the fastenings, chain plates, chains, and anchors of your ship;

all those who can make rope and all the people who grow fibers

for your rope; all the people who grow, spin, and weave together

the fabrics for your sails. Thus, all the skilled people of the

nation had to be employed in the building and outfitting of your

ship. In addition you had to command all the farmers who produced

the food to feed not only themselves but also to feed all those

skilled people while they built the ship—and to feed all

your army and all your court. So there was no way you could possibly

produce one of these great ships unless you were very, very powerful.

Even then, in building ships, there were

many essential materials that you didn't have in your own nation

and so had to purchase from others. You also needed working cash—money

to cope with any and all unforeseen events that could not be

coped with by use of muscle or the sword—money to trade

with. It was at this stage of your enterprise that the banker

entered into the equation of power.

Up until 1500 B.C. all money was cattle,

lambs, goats, or pigs—live money that was real life-support

wealth, wealth you could actually eat. Steers were by far the

biggest food animal, and so they were the highest denomination

of money. The Phoenicians carried their cattle with them for

trading, but these big creatures proved to be very cumbersome

on long voyages. This was the time when Crete was the headquarters

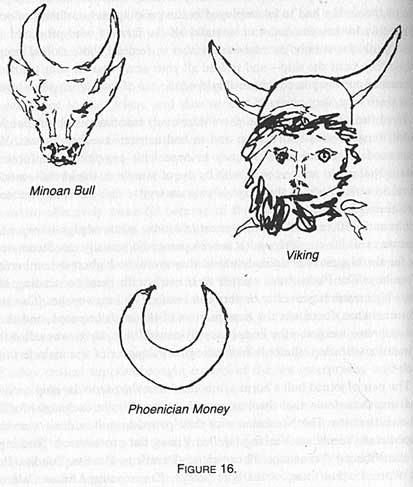

of the big-boat people and their new supreme weapon—the

lines-of-supply-control ship. Crete was called the Minoan civilization,

the bull civilization, worshippers of the male fertility god.

The pair of joined bull's horns symbolized

that the particular ship carried real-wealth traders—that

there were cattle on board to be exchanged for local-wealth items.

The Norsemen with their paired-horn headdress were the Phoenician,

Veenetian, Veeking (spelled Viking but pronounced "Veeking"

by the Vikings). Veenetians, Phoenicians. (Punitians, Puntits,

Pundits. Punic Wars. Punt = boat = the boat people. Pun

in some African Colored languages means "red," as in

Red Sea.). The Veekings were simply the northernmost European

traders. The Veekings, Veenitians, Feenicians, Friesians—i.e.,

Phoenicians, Portuguese—were cross-breeding water-world

people.

Graduating from carrying cattle along

for trading in 1500 B.C. the Phoenicians invented metal money,

which they first formed into iron half-rings that looked like

a pair of bull's horns. (Many today mistake them for bracelets.)

Soon the traders found that those in previously unvisited foreign

countries had no memory of the cattle-on-board trading days and

didn't recognize the miniature iron bull horn. If metal was being

used for trading, then there were other kinds of metal they preferred

trading with people—silver, copper, and gold were easy to

judge by hefting and were more aesthetically pleasing than the

forged iron bull horn symbols.

This soon brought metal coinage into

the game of world trading, with the first coin bearing the image

of the sovereign of the homeland of the Phoenicians.

This switch to coinage occurred coincidentally

at just about the same time as the great changeover from city-state

dominance to line-of-supply dominance of the power-structure

group controlling most of world affairs. This was the time when

the Phoenicians began trading with people of so many different

languages that, in need of a means of recording the different

word sounds made by people around the world, the Phoenicians

invented phonetic spelling—Phoenician spjelling—which

pronounced each successive sound separately and invented letter

symbols for each sound. With phonetic spelling human written

communication changed very much—from the visual-metaphor-concept

writing of the Orient, accomplished with complex idea-graphics

(ideographs), several of which frequently experienced, generalized

cartoons told the whole story visually. It was a big change from

ideographs to the Phoenicians' phonetic spelling, wherein each

letter is a single sound—having no meaning in itself—and

whereby it took several sounds to make a whole word and many

such words to make any sense—i.e., a sentence. This is the

historical event that Ezra Pound says coincides with the story

of the Tower of Babel. Pound says that humanity was split into

a babble of individually meaningless sounds while losing the

conceptual symbols of whole ideas—powerful generalizations.

You had to become an expert to understand the phonetic letter

code. The spelling of words excluded a great many people from

communicating, people who had been doing so successfully with

ideographs.

This gradual alteration of world trading

devices from cattle to gold brought about the world-around development

of pirates who, building small but swift craft, could on a dark

night board one of the great merchant ships just before it reached

home, richly laden after a two-year trip to the Orient, and take

over the ship and, above all, its gold. With the gold captured,

the pirates often burned the vanquished ship.

As already mentioned in our Introduction,

it was in 1805, 200 years after the founding of the East India

Company, that the British won the Battle of Trafalgar, giving

them dominance of all the world's lines of supply. They now controlled

the seas of the world. It was said by world people that the British

Empire became the first empire in history upon which "the

sun never set." In order to get their gold off the sea and

out of reach of the pirates, the British made deals with the

sovereigns of all the countries around the world with whom they

traded, by which it was agreed from then on to keep annual accounts

of their intertrading and at the end of the year to move the

gold from the debtor's bank in London to the creditor's bank

in London to balance the accounts. In this way they kept the

gold off the ocean and immune to sea pirate raiding. This brought

about what is now called the "balance of trade" accounting.

The international trading became the

most profitable of all enterprises, and great land-''owners"

with clear-cut king's "deeds" to their land went often

to international gold moneylenders. The great land barons underwrote

the building of enterprisers' ships with their cattle or other

real wealth, the regenerative products of their lands, turned

over to the lender as collateral.

If the ship did come back, both the enterpriser

and the bankers realized a great gain. The successful ship venturer

paid the banker back, and the banker who had been holding the

cattle as collateral returned them to their original proprietor.

But during the voyage (usually two years to the Orient and back

to Europe) the pledged cattle had calves, "kind" (German

for "child"), and this is where the concept of interest

originated, which was payable "in kind"—the cattle

that were born while the collateral was held by the banker were

to belong to the banker.

When the Phoenicians shifted their trading

strategy from carrying cattle to carrying metal money, the metal

money didn't have little money—"kind"—but

the idea of earned interest persisted. This meant that the interest

was deducted from the original money value, and this of course

depreciated the capital equity of the borrower. Thus, metallic

equity banking became a different kind of game from the original

concept.

In twentieth-century banking the depositors

assume that their money is safely guarded in the vaulted bank,

especially so in a savings bank, whereas their money is loaned

out, within seconds after its depositing, at interest payable

to the banker which is greater than the interest paid to the

savings account depositor and, since the metal or paper money

does not produce children—"kind"—the banker's

so-called earned share must, in reality, be deducted from the

depositor's true-wealth deposit.

The merchant bankers of Venice came to

underwrite the Venetians' (the Phoenicians') voyaging ventures.

Such international trade financing swiftly became the big thing

in the banking game. The "Merchant of Venice"—Shylock

and his "pound of flesh forfeit" of the debtor—was

Shakespeare's way of calling attention to the fact that the bankers'

"interest" was in reality depleting the life-support

equity of both the depositors and the borrowers.

It was the financing of such international

voyaging, trading, and individual travel as well as of vaster

games of governmental takeovers that built the enormous wealth-controlling

fortunes of early European private banking families. It was under

analogous circumstances of financing inter-American-European

trade that, in the late nineteenth century, J. P. Morgan became

a man of great power. By having his banking houses in Paris and

London, Philadelphia and New York, he was able not only to finance

people's foreign travel, all their intershipment of goods, and

to give letters of credit, but also to finance and control major

"new era" railroading, shipbuilding, mining, manufacturing,

and energy-generating enterprises in general.

Such powerful banking gave insights regarding

the degrees of risks that could be taken. The people doing the

risking came to the banker for advice. In such a manner J. P.

Morgan developed the most powerful financing position in America,

as society went from wooden ships to steel ships and the concomitant

iron mining, blast furnace building, and steel rolling mill development,

as well as the making of boilers and engines, electric generators,

and air conditioning systems.

To better understand the coming of world

power structure into North American affairs, we will switch back

from the nineteenth to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries,

to the opening up of North America and the American socioeconomic

scene. The European colonization occurred in several major ways.

The Spanish way was accomplished with

vast haciendas—grants from the king to powerful supporters.

The hacienda development began in Central America and Mexico

and expanded northward into California.

The British king also gave vast plantation

grants to royal favorites on the North American southeastern

coast, below the freezing line.

The French came to two parts of North

America: (1) to the Gulf of Mexico-Mississippi delta, where exiled

prisoners were dumped, and (2) to the St. Lawrence area of Canada,

whence they moved westward via the Great Lakes, then southward

on the Mississippi to join with these lower Mississippi colonists

exploring northward and westward on the Mississippi.

British sovereign grants were also being

given on the northeastern coast, where it was much colder and

where existence was much more difficult. Because it was much

more difficult to colonize, the royal favorites who received

large land grants from the British king in the north did everything

they could to encourage colonization of any kind by others, who

bought their land from their landlords. The Pilgrims and other

people of religious conviction found the freedom of thought-and-act

to warrant hazarding their lives in that cold-winter wilderness.

On the northeast coast of North America the individuals who did

the colonizing were not the landowners, who remained safely in

Europe. In the south the royal-favorite landowners themselves

occupied and personally operated many of the great plantations.

Though motivated by distinctly different

northern and southern reasons for doing so, we have the east-coast

North American British-blood people breaking away from the Old

World through the American Revolution.

In our tracing of the now completely

invisible world power structures it is important to note that,

while the British Empire as a world government lost the American

Revolution, the power structure behind it did not lose the war.

The most visible of the power-structure identities was the East

India Company, an entirely private enterprise whose flag as adopted

by Queen Elizabeth in 1600 happened to have thirteen red and

white horizontal stripes with a blue rectangle in its upper lefthand

corner. The blue rectangle bore in red and white the superimposed

crosses of St. Andrew and St. George. When the Boston Tea Party

occurred, the colonists dressed as Indians boarded the East India

Company's three ships and threw overboard their entire cargoes

of high-tax tea. They also took the flag from the masthead of

the largest of the "East Indiamen"—the Dartmouth.

George Washington took command of the

U.S. Continental Army under an elm tree in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The flag used for that occasion was the East India Company's

flag, which by pure coincidence had the thirteen red and white

stripes. Though it was only coincidence, most of those present

thought the thirteen red and white stripes did represent the

thirteen American colonies—ergo, was very appropriate—but

they complained about the included British flag's superimposed

crosses in the blue rectangle in the top corner. George Washington

conferred with Betsy Ross, after which came the thirteen white,

five-pointed stars in the blue field with the thirteen red and

white horizontal stripes. While the British government lost the

1776 war, the East India Company's owners who constituted the

invisible power structure behind the British government not only

did not lose but moved right into the new U.S.A. economy along

with the latter's most powerful landowners.

By pure chance I happened to uncover

this popularly unknown episode of American

history. Commissioned in 1970 by the Indian government to

design new airports in Bombay, New Delhi, and Madras, I was visiting

the grand palace of the British fortress in Madras, where the

English first established themselves in India in 1600. There

I saw a picture of Queen Elizabeth I and the flag of the East

India Company of 1600 A.D., with its thirteen red and white horizontal

stripes and its superimposed crosses in the upper corner. What

astonished me was that this flag (which seemed to be the American

flag) was apparently being used in 1600 A.D., 175 years before

the American Revolution. Displayed on the stairway landing wall

together with the portrait of Queen Elizabeth I painted on canvas,

the flag was painted on the wall itself, as was the seal of the

East India Company.

The supreme leaders of the American Revolution

were of the southern type—George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

Both were great land-owners with direct royal grants for their

lands, in contradistinction to the relatively meager individual

landholdings of the individual northern Puritan colonists.

With the Revolution over we have Alexander

Hamilton arguing before the Congress that it was not the intention

of the signers of the Declaration of Independence that the nation

so formed should have any wealth. Wealth, Hamilton argued—as

supported by Adam Smith—is the land, which is something

that belonged entirely to private individuals, preponderantly

the great landowners with king-granted deeds to hundreds and

sometimes thousands of square miles, as contrasted to the ordinary

colonists' few hundreds of acres of homestead farms.

Hamilton went on to argue that the United

States government so formed would, of course, need money from

time to time and must borrow that money from the rich landowners'

banks and must pay the banks back with interest. Assuming that

the people would be benefited by what their representative government

did with the money it borrowed, the people gladly would be taxed

in order to pay the money back to the landowners with interest.

This is where a century-and-a-half-long game of "wealth''-poker

began—with the cards dealt only to the great landowners

by the world power structure.

Obviously, very powerful people had their

land given to them by the king and not by God, but the king,

with the church's approbation, asserted it was with God's blessing.

This deed-processing produced a vast number of court decisions

and legal precedent based on centuries and centuries of deed

inheritances. Thus, landlord's deeds evolved from deeds originally

dispensed from deeds of war. Then the great landlords loaned

parcels of their lands to sharecropping farmers, who had to pay

the landlord a tithe, or rent, and "interest" out of

the wealth produced by nature within the confines of the deeded

land. The landlord had his "tithing" barn within which

to store the grains collected in the baskets (fiscus is

Latin for "basket"; thus the fiscal year is that which

winds up within the basketed measuring of the net grains harvested).

The real payoff, of course, was in regenerative metabolic increments

of the botanical photosynthetic impoundment of Sun radiation

and hydrocarbon molecules' structuring and proliferation through

other hydrogenic and biological interaccommodations. Obviously

none of this natural wealth-regenerating and -multiplying process

was accreditable to the landlords.

When I was young, there were people whom

everybody knew to be very "wealthy." Nobody had the

slightest idea of what that "wealth" consisted, other

than the visible land and the complex of buildings in which the

wealthy lived, plus their horses, carriages and yachts. The only

thing that counted was that they were "known to be"

enormously wealthy. The wealthy could do approximately anything

they wanted to do. Many owned cargo ships. However, the richest

were often prone to live in very unostentatious ways.

Of course, money was coined and the paper

equivalents of metallic coinage were issued by the officers of

banks of variously ventured private-capital-banking-type land

systems. Enterprises were underwritten by wealthy landowners,

to whom shares in the enterprises were issued and, when fortunate,

dividends were paid. "Rich" people sometimes had their

own private banks—as, for instance, J. P. Morgan and Company.

Ordinary people rushed to deposit their earnings in the wealthy

people's banks.

For all the foregoing reasons nobody

knew of what the wealth of the wealthy really consisted, nor

how much there was of it. There were no income taxes until after

World War I. But the income tax did not disclose capital wealth.

It disclosed only the declared income of the wealthy. The banks

were capitalized in various substantial amounts considered obviously

adequate to cover any and all deposits by other than the bankers

involved in proclaiming the capital values. These capital values

were agreed upon privately between great landowners based on

equities well within the marketable values of small fractions

of their vast king-deeded landholdings.

"The rich get richer and the poor

get children" was a popular song of the early 1920s. Wages

were incredibly low, and the rich could get their buildings built

for a song and people them with many servants for another song.

But, as with uncalled poker hands, nobody ever knew what the

"wealthy" really had. I was a boy in a "comfortably

off" family, not a "wealthy" family—not wealthy

enough to buy and own horses and carriages. To me the wealthy

seemed to be just "fantastically so."

This brings us to World War I. Why was

it called the First World War? All wars until this time

had been fought in the era when land was the primary wealth.

The land was the wealth because it produced the food essential

to life. In the land-wealth era of warring the opposing forces

took the farmers from the farms and made soldiers of them. They

exhausted the farm-produced food supplies and trampled down the

farms. War was local.

In 1810, only five years after Malthus's

pronouncement of the fundamental inadequacy of life support on

planet Earth, the telegraph was invented. It used copper wires

to carry its messages. This was the beginning of a new age of

advancing technology. The applied findings of science brought

about an era in which there was a great increase of metals being

interalloyed or interemployed mechanically, chemically, and electrolytically.

Metals greatly increased the effectiveness of the land-produced

foods. The development of nonrusting, hermetically sealed tin

cans made possible preservation and distribution of foods to

all inhabited portions of our planet Earth. All the new technology

of all the advancing industry, which was inaugurated by the production

of steel in the mid-nineteenth century, required the use of all

the known primary metallic elements in various intercomplementary

alloyings. For instance tin cans involved tin from the Malay

straits, iron from West Virginia mines, and manganese from southern

Russia.

The metals were rarely found under the

farmlands or in the lands that belonged to the old lords of the

food-productive lands. Metals were found—often, but not

always, in mountains—all around the world, in lands of countries

remote from one another. Mine ownerships were granted by governments

to the first to file claims.

It was the high-seas, intercontinental,

international trafficking in these metals that made possible

the life-support effectiveness of both farming and fishing. The

high-seas trafficking was mastered by the world-around line-of-supply

controllers—the venturers and pirates known collectively

as the British Empire. This world-around traffic was in turn

financed, accounted, and maximally profited in by the international

bankers and their letters of credit, bills of exchange, and similar

pieces of paper. International banking greatly reduced the necessity

for businessmen to travel with their exported goods to collect

at the importer's end. Because the world-around-occurring metals

were at the heart of this advance in standards of living for

increasing numbers of humans all around the world, the struggle

for mastery of this trade by the invisible, behind-the-scenes-contending

world power structures ultimately brought about the breakout

of the visible, international World War I.

The war was the consequence of the world-power-structure

"outs" becoming realistically ambitious to take away

from the British "ins" the control of the world's high-seas

lines of supply. The "outs" saw that the British Navy

was guarding only the surface of the sea and that there were

proven new inventions—the submarine, which could go under

the water, and the airplane, which could fly above the water—so

the behind-the-scenes world-power-structure "outs"

adopted their multidimensional offensive strategy against the

two-dimensional world-power-structure "ins." The invisible-power-structure

"outs" puppeted the Germans and their allies. The invisible-power-structure

"ins" puppeted Great Britain and her allies. With their

underwater strategies the "outs" did severely break

down the "ins' " line of supply.

J. P. Morgan was the visible fiscal agent

for the "in" power structure, operating through Great

Britain and her allies. The 1914 industrial productivity in America

was enormous, with an even more enormous amount of untapped U.S.

metallic resources, particularly of iron and copper, as backup.

Throughout the nineteenth century all

the contending invisible world power structures invested heavily

in U.S.A.-enterprise equities. Throughout that nineteenth century,

the vast resources of the U.S.A. plus the new array of imported

European industrial tooling, the North American economy established

productivity. The U.S.A. economy took all the industrial machinery

that had been invented in England, Germany, France, and Europe

in general and reproduced it in America with obvious experience-suggested

improvements.

In 1914 World War I started in the Balkans

and was "joined" in Belgium and France on the European

continent. The British Isles represented the "unsinkable

flagship" of the high-seas navy of the masters of the world

oceans' lines of supply. The "unsinkable flagship"

commanded the harbors of the European customers of the high-seas-line-of-supply

control. If the line of supply that kept the war joined on the

European continent broke down completely, then the "outs"

would be able to take the British Isles themselves, which, as

the "flagship" of the "ins," would mean the

latter's defeat.

In 1914, three years before the U.S.A.

entered the war, J. P. Morgan, as the "Allies' " fiscal

agent, began to buy in the U.S.A. to offset the line-of-supply

losses accomplished by the enemy submarines. Morgan kept buying

and buying, but finally, on the basis of sound world-banking

finance, which was predicated on the available gold reserve,

came the point at which Morgan had bought for the British and

their allies an amount of goods from the U.S.A. equaling all

the monetary bullion gold in the world available to the "ins'

" power structure. Despite this historically unprecedented

magnitude of the Allied purchasing it had only fractionally tapped

the productivity of the U.S.A. So Morgan, buying on behalf of

England and her allies, exercised their borrowing "credit"

to an extent that bought a total of goods worth twice the amount

of gold and silver in the world available to the "ins."

As yet the potential productivity of the U.S.A. was but fractionally

articulated. Because the "ability to pay later" credit

of the Allied nations could not be stretched any further, the

only way to keep the U.S.A. productivity flowing and increasing

was to get the U.S.A. itself into the war on the "ins' "

side, so that it would buy its own productivity in support of

its own war effort as well as that of its allies.

By skillful psychology and propaganda

the "ins" persuaded America that they were fighting

"to save democracy." I recall, as one of the youth

of those times, how enthusiastic everyone became about "saving

democracy." Immediately the U.S.A. government asked the

British and their allies, "What do you need over there?"

The "ins" replied, "A million trained and armed

men, and the ships to carry them to France, and many, many new

ships to replace the ships that have been sunk by submarines.

We need them desperately to keep carrying the tanks and airplanes,

weapons, and munitions to France." The "ins" also

urgently requested that the U.S. Navy be increased in strength

to equal the strength of the British Navy and therewith to cope

with the German submarines, "while our British Navy keeps

the German high-seas fleet bottled up. We want all of this from

America."

America went to work, took over and newly

implemented many of the U.S. industries, such as the telephone,

telegraph, and power companies, and produced all that was wanted.

For the first time in history, from 1914 to 1918, humanity entered

upon a comprehensive program of industrial transformation and

went from wire to wireless communications; from tracked to trackless

transportation; from two-dimensional transport to four-dimensional;

from visible structuring and mechanical techniques to invisible—atomic

and molecular—structuring and mechanics.

Within one year the million armed and

trained U.S.A. soldiers were safely transported to France without

the loss of one soldier to the submarines. Arrived in France,

they entered the line of battle. With the line of supply once

more powerfully re-established by the U.S. Navy and its merchant

fleet, it became clear that the "ins" were soon going

to win.

J. P. Morgan, now representing the "allied"

power structures' capitalist system's banks as well as serving

as the Allies' purchasing agent, said to the American Congress,

"How are you going to pay for it all?" The American

Congress said, "What do you mean, pay for it? This is our

own wealth. This is our war to save democracy. We will win the

war and then stop the armaments production." Morgan said,

"You have forgotten Alexander Hamilton. The U.S. government

doesn't have any money. You're going to pay for it all right,

but since you don't have any money, you're going to have to borrow

it all from the banks. You're going to borrow from me, Mr. Morgan,

in order to pay these vast war bills. Then you must raise the

money by taxes to pay me back."

To finance these enormous payments Mr.

Morgan and his army of lawyers invented—for the U.S. government—the

Liberty Loans and Victory Loans. Then the U.S. Congress invented

the income tax.

With the U.S. Congress's formulating

of the legislation that set up the scheme of the annual income

tax, "we the people" had, for the first time, a little

peek into the poker hands of the wealthy. But only into the amount

of their taxable income, not into the principal wealth cards

of their poker game.

During World War I, U.S. industrial production

had gone to $178 billion. With only $30 billion of monetary gold

in the world, this monetary magnitude greatly exceeded any previously

experienced controllability of the behind-the-scenes finance

power structure of the European "Allies."

World War I over, won by the Allies,

all the countries on both sides of the warring countries are

deeply in debt to America. Because the debt to the U.S.A. was

twice that of all the gold in the "ins' " world, all

the countries involved in World War I paid all their gold to

the U.S.A. Despite those enormous payments in gold all the countries

were as yet deeply in debt to the U.S.A. Thereafter all those

countries went off the gold standard.

All the monetary gold bullion paid to

the U.S.A. was stored in the mountain vaults of Fort Knox, Kentucky.

International trade became completely immobilized, and the U.S.A.

found itself having unwittingly become the world's new financial

master. Swiftly it arranged vast trading account loans to the

foreign countries. This financing of foreign countries' purchasing

by the U.S.A. credit loans started an import-export boom in the

U.S.A., followed by an early 1920s recession and another boom;

then, the Great Crash of 1929.

The reasons for the Great Crash go back

to the swift technological evolution occurring in the U.S.A.

between 1900 and the 1914 beginning of World War I and the U.S.A.'s

entry into it in 1917. Most important amongst those techno-economic

evolution events are those relating to electrical power. Gold

is the most efficient conductor of electricity, silver is the

next, and copper is a close third. Of these three gold is the

scarcest, silver the next, then copper. Though relatively scarce,

copper is the most plentiful of the good electrical conductors.

Copper is also nonsparking and therefore makes a safe casing

for gunpowder-packed bullets and big gun shells. As a consequence

of these conditions, in the one year, 1917, more copper was mined,

refined, and manufactured into wire, tubing, sheet, and other

end products than in the total cumulative production of all the

years of all human history before 1917.

With the war over all the copper that

had been mined and put into generators and conductors did not

go back into the mines nor did it rot.

World War I was not an agrarian, but

an inanimate-energy and power-driven, industrial-production war—with

the generating power coming from Niagara and other waterfalls

as well as from coal and petroleum. For the first time the U.S.A.

was generating power with oil-burning steam turbines.

When the war was over, all this power-production

equipment was still in prime operating condition. There was enormous

potential productivity—a wealth of wealth-producing capability

that had never before existed, let alone as a consequence of

war. The production capacity that had been established was so

great as to have been able to produce, within a two-year span,

all those ships, trucks, and armaments. What was the U.S.A. economy

going to do with its new industrial gianthood? It was the vastness

of this unexpected, government-funded production wealth and its

ownership by corporate stockholders that generated many negative

thoughts about the moral validity of war profiteering.

There were many desirable and useful

items that could be mass-produced and successfully marketed.

Young people wanted automobiles, but automobiles were capital

equipment. In 1920 capital equipment was sold only for cash.

There were enough affluent people in post-World-War-I U.S.A.

to provide an easy market for a limited production of automobiles.

In 1920 there were no bank-supported time payment sales in the

retail trade. The banks would accept chattel mortgages and time

payments on large mobile capital goods, such as trucking equipment,

for large, rich corporations. Banks would not consider risking

their money on such perishable, runaway-with-able capital equipment

as the privately owned automobile.

Because the banks would not finance the

buying of automobiles and so many money-earning but capital-less

young people wanted them, shyster loaners appeared who were tough

followers of their borrowers when they were in arrears. Between

the ever-increasing time-payment patronage and the affluent,

a market for automobiles was opening that could support mass

production.

In 1922 there were about 125 independent

automobile companies. They were mostly headed by colorful automobile-designing

and -racing individuals for whom most of the companies were named.

They survived by individually striving each year to produce an

entirely new and better automobile, most of which were costly.

Many accepted orders for more than they had the mechanical capability

to produce. Their hometown financiers would back these auto-designing

geniuses so that they could buy better production tooling and

build larger factories. Wall Street sold swiftly increasing numbers

of shares in auto companies. More and more of them went broke

for lack of production, distribution, and maintenance experience

on the part of the auto-designer managements.

In 1926 the Wall Street brokerage house

of Dillon, Read and Co. made a comprehensive cost study of the

auto-production field. They found that 130,000 cars a year was,

in 1926, the minimum that could be accounted as mass production

and sold at production prices. Any less production had to carry

a much higher price tag. To warrant the latter, the cars had

to be superlatively excellent. The English-built Rolls-Royce

brought the highest price on the American market. There was fierce

competition among Packard, Peerless, Cadillac, Pierce-Arrow,

Locomobile, Lozier, Leiand, and others for the top American car.

All of those premium cars' frames, bodies, engines, and parts

were manufactured within their own factories. There were several

in-between classes, such as that of the Buick. Most of the 100

or so cars in this intermediate range were assembled from special

engines, frames, and other parts made by independent manufacturers.

The mortality in auto companies was great.

Dillon, Read led Wall Street out of its dilemma by buying several

almost bankrupt companies, closely located to one another, such

as those of the Dodge family, whose joint production capacity

topped the 130,000 units per year mass-production figure. They

named their new venture the Chrysler Company. Dillon, Read fired

the auto company presidents, who were primarily interested in

new-car-designing, and replaced them with production engineers.

Wall Street followed suit and put in production engineers as

presidents of all the auto companies—except Ford, who owned

his company outright and had no obligation to Wall Street and

its legion of stock buyers. Old Henry himself was already the

conceiver, initiator, and artist-master of mass production.

Because the American public was in love

with the annual automobile shows, the Wall Street financiers

who had thrown out all the colorful auto-designer presidents

started a new game by setting up the Madison Avenue advertising

industry, which hired artists who knew how to use the new (1920)

airbrush to make beautiful drawings of only superficially—not

mechanically—new dream cars. They made drawings of

the new models, which required only superficial mudguard and

radiator changes with no design changes in the hidden parts.

Parts were purchased by the big companies from smaller, highly

competitive parts manufacturers operating in the vicinity of

Detroit.

This was the beginning of the downfall

of the world-esteemed integrity of Yankee ingenuity, which was

frequently, forthrightly, and often naively manifest in American

business. Big business in the U.S.A. set out to make money deceitfully—by

fake "new models"—and engineering design advance

was replaced by "style" design change.

In the late twenties first Ford and then

General Motors instituted their own time-financing corporations.

The bankers of America said, "Let them have it, they'll

be sorry—autos, phew! We don't want to go around trying

to recover these banged-up autos when the borrower is in default."

The bankers said, "It is very immoral to buy automobiles

'on time.' They are just a luxury."

What the bankers did like to support

in the new mass productivity was tractor-driven farm machinery.

Farm machinery was easy to sell. As the farmer sat atop the demonstration

plowing or harvesting equipment, with its power to go through

the fields doing an amount of work in a day equal to what had

previously taken him weeks, he said to himself, "I can make

more money and also take it a little easier." So the bankers

approved the financing of the production and marketing of the

farm machinery. They held a chattel mortgage on the machinery

and a mortgage on the farmland itself and all its buildings.